|

Refreshing as a Great Rock

By Rick Kennedy

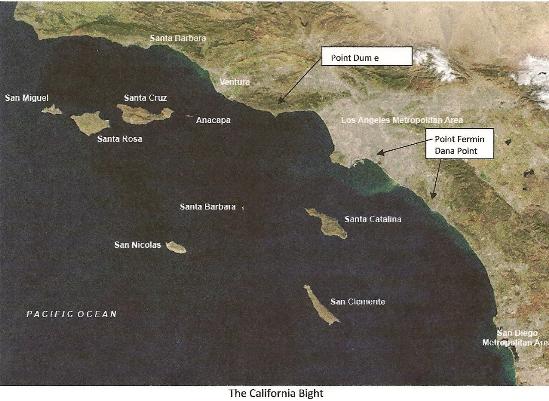

Sailing up the California Bight heightens appreciation for big rocks. I rounded Point Loma, the four hundred foot high, six mile long, rock that guards San Diego Bay, early on a July fourth morning to begin a three day sail, north by northwest, up to Channel Islands National Park where I would meet my family and friends for a camping trip. As the wind filled in during the morning, I sailed close hauled, everything as tight as possible, looking for Dana Point, the next rock in my rock-hop up the coast.

My boat, Boethius, is a twenty-four foot, long-keel, drop-centerboard, Yankee Dolphin. Balance the sails, stay seated in one place, and she will steer herself for hours. On this trip she and I sailed past Costa Mesa where she was built almost forty years ago. Her name comes from a textbook writer who was executed in 524 by Theodoric, king of what is now Italy. Boethius, while awaiting his fate, wrote a short, beautiful book called The Consolation of Philosophy. The Goths apparently executed him by slowly tightening a tourniquet around his skull.

Sailing can be stressful. The first day of my trip was a fourteen hour push into the current and wind. I was happy, but during the long course of the afternoon I increasingly allowed myself to get anxious. I was straining to point as high as possible while attaining as much speed as possible. I wanted to get to Dana Point before dark. This being the Fourth of July I expected a packed anchorage and worried about my arrival time. As the afternoon waned, I could see the high cliff of Dana Point in the distance. Too often I looked at my watch.

Back before the railroads, when the economy of California was oriented to maritime trade, the Southern California "points" were much sought after because some of them protected a safe anchorage. Southern California has a long coast with few protected anchorages. There are no luxurious deep river mouths, only one fully protected bay, and the currents, winds, and rolling swells from the northwest make most of the coast an uninviting lee shore. Before the dredging of man-made harbors, a sailor looked for the tall rocky mounds that jut out into the Pacific behind which was protection from a northwest wind and swell. Three hundred miles of coastline offered five good rocks: Points Conception, Dume, Fermin, Dana, and Loma.

Like all ancient and early modern sailors on the California coast, I could see the long sheer cliff for a long time before arriving. Happily, I got to the modern man-made harbor entrance at dusk, anchored with the sun setting, ate dinner in the cockpit after dark, and watched fireworks for dessert.

Richard Henry Dana, author of Two Years Before the Mast, wrote of anchoring in the lee of this same cliff in 1835. His boat, the Pilgrim, came to load hides collected at nearby mission San Juan Capistrano. Dana was a kid, running away from college, and, when highly frustrated by a tyrannical captain, he formed an emotional attachment to the place that now bears his name. He described it as "the only romantic spot in California." Thinking of this cliff he wrote the line: "as refreshing as a great rock in a weary land." I suspect that many a literature class has pondered that line, "as refreshing as a great rock," but a coastal sailor knows what he means. I was refreshed by that same rock after a long day.

The next morning I motored out from under the lee of Dana Point, and, when the wind filled in, I was again sailing close hauled, north by northwest. By early afternoon I could see Point Fermin dead ahead. But I did not want to go there. I would round up into its lee on the way home. On the trip north I wanted to get over to Santa Catalina Island, one of the great, steep, rocks off the coast. I planned to stay overnight snuggled in tight next to the rock.

There is only one well-protected bay in all of the Channel Islands. This little used bay is called Catalina Harbor and protected by great, tall, rocks. Awkwardly for coastal sailors, it is on the far side of the island. But anyone wanting to anchor for a whole winter, be they explorers, pirates, smugglers, or those avoiding dock fees, looks to Catalina Harbor as a safe haven.

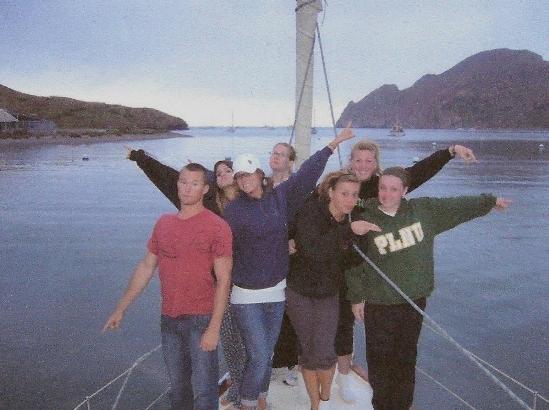

Every May I teach a California History class that sails a Bavaria 46 named Wizard for eleven days through the Channel Islands. When we pick up a mooring in Catalina Harbor I teach about the scholarly problem of explorer Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo's death. We know he died after an Indian skirmish on one of the Channel Islands, but we don't know which one. The best guess is that Cabrillo was wintering in this harbor in 1542-43. We scholars speculate that he would have wanted the protection of the high rocks.

Sitting on deck with the students, we read sixteenth-century accounts of the last days of Cabrillo, we survey the topography of the harbor, and we practice our historical imagination, offering our best guesses about where Cabrillo's boat would have anchored, where he would have been hurt during the Indian skirmish, and where his crew would have buried him. The exercise ends, however, with me pointing toward the massive rock at the entrance to the little bay, reminding the students that all our speculations are premised on the assumption that a sailor like Cabrillo would have sought to winter close in under the protection of that big rock.

Student's speculating about where Cabrillo is buried in the lee of the rocks protecting the entrance to Catalina Harbor, Santa Catalina Island.

But I was alone this trip in a much smaller boat. I filled my outboard's gas tanks the next morning at the Isthmus behind Catalina Harbor and headed northwest into glassy seas. I was planning, when the wind filled in, to anchor that evening in the lee of Anacapa Island—a small set of steep rocks. However, no wind filled in, so I motored all afternoon across glassy seas straight toward the east end of Santa Cruz Island. At 4pm with my destination only twelve and a half miles away the wind decided to fill in fast and hard from dead ahead. The outboard pushed me into stirred up seas. I became wet and cold with spray. There is a swath of water called "Windy Lane" that cuts through the Santa Barbara Channel north of the islands. Wind rushes around Point Conception and sweeps past the islands toward Ventura. I was in the channel between Santa Cruz and Anacapa islands getting beaten up by an offshoot from Windy Lane. I could see, however, not far ahead the large rock that would give me protection for the night.

Three hours later I pushed out of the choppy, spray-filled, wind into the relative calm behind Cavern Point. The small rocky beach of Scorpion Ranch, watched over by the National Park Service, was close. My family and friends would arrive tomorrow.

Robinson Jeffers, maybe California's best poet, wrote a lot about rocks. In poems such as "Carmel Point" and "Continent's End" Jeffers wrote as if coastal granite is the standard by which humanity is measured. He wrote of the "insolent quietness of stone." In a poem called "Oh, Lovely Rock" he recounted an instance of staring at the face of a cliff, feeling "its intense reality with love and wonder." Sailing north by northwest up the California Bight teaches appreciation for rocks. The wind, current, and swells seem to be against you. Only the great stoic rocks offer solace.

Boethius in the lee of Cavern Point at Scorpion Anchorage, Santa Cruz Island

Click here to go to Boethius' home page

*********************

|

|